The 16mm Honesty of 'Original Cast Album: Company'

One Of Sondheim's Masterpieces, Through the Eyes of D.A. Pennebaker

During his audio commentary, recorded by the Criterion Collection for their 2021 Blu-Ray release, composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim revealed that, prior to the recording of “The Ladies Who Lunch,” D.A. Pennebaker, who had been documenting the day’s work, was beginning to pack up his equipment. He was getting ready to leave, after all, it was somewhere around 2 AM, and he was exhausted from the day of filming. He stopped, however, when he heard the strained, equally tired voice of Elaine Stritch begin to force its way through the song. He decided to stay for a little while longer. And what he captured is among the most insightful, and triumphant, documentary footage ever recorded.

It should come as no surprise that a documentarian as talented and experienced as Pennebaker was able to make Original Cast Album: Company so interesting. But it’s truly remarkable how much tension he’s able to wring out of what are fairly procedural activities.

The documentary opens with a sound technician running cables, connecting power, and setting up for recording. He’s then joined by the record’s producer, Thomas Z. Shepard, who then argues with him over the number of percussionists they had in the studio (“You mean to say we have a timpanist, a real drummer, and two percussion men? Impossible”).

Shepard is then joined by director Harold (Hal) Prince, writer George Furth, composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim, and the cast of the show, including Elaine Stritch and Dean Jones. Their shared goal is to record the album for what would go down as one of Broadway’s greatest shows. The dramatic tensions seem low — not that that’s something Pennebaker wouldn’t be able to use, see Don’t Look Back — but in reality, they’re quite high. As one of the singers puts it, “this is the end all and the be all of these songs.”

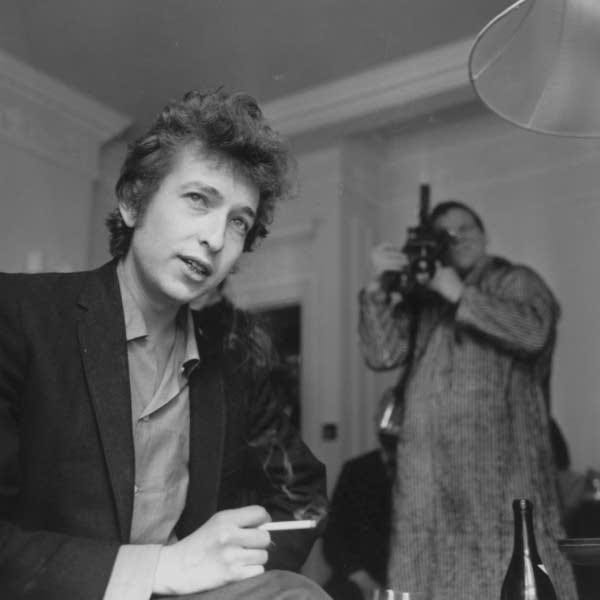

Stephen Sondheim (Left) and Thomas Shepard (Right) in the tech room during the recording of one of Sondheim’s songs.

It’s moments like these — shot with Pennebaker’s signature over-the-shoulder rig, which he used to make natural, off-the-cuff conversation with a subject without having to set up his equipment; Sondheim said it made everyone more comfortable with the camera; you were speaking to a person, not a machine — that makes this documentary so unique: it’s a quirky, naturalistic view into the minds of great artists. Which only works because Pennebaker is so genuine in his methods, rather than simply showing the recording of one song, he shows take, after take, after take, after take to drive home the idea of process; it’s the story of the making of a record, not just the final product.

Somewhere around the half-way point, the crew takes a break for lunch. Sondheim, Furth, and Prince are discussing the origin of the show in Furth’s writing, and how Prince suggested they make it a musical, and Sondheim, who famously responded with, without any further consideration, “I’ll do it.” Elaine Stritch is sitting at the end of the table, observing, and Pennebaker is, presumably, kneeling on the floor. Shepard then comes over and, after greeting Stritch, informs the team that the recording will be done at roughly 3 in the morning; “Everybody smile.”

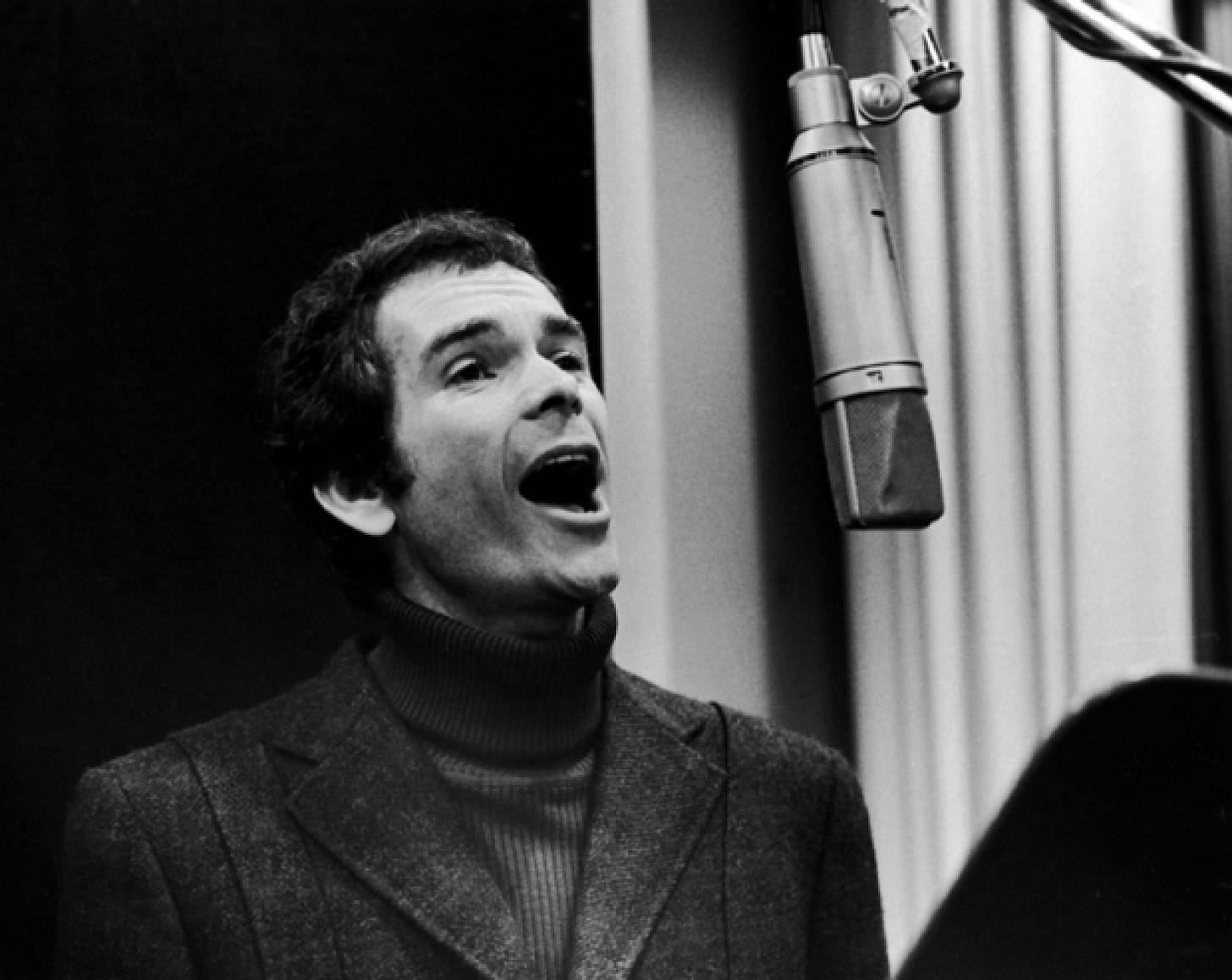

D.A Pennebaker (Back right) using his aforementioned “over-the-shoulder” rig to film Bob Dylan (Left) on the set of Don’t Look Back, his 1967 documentary following Dylan on his first European tour.

Scheduled for immediately after lunch was Stritch, to record “The Ladies Who Lunch.” But Jones expressed concern over his after-midnight time slot for “Being Alive,” as he thought his voice would be too tired to perform well. Stritch, being ever confident, offered to trade with him, taking the early morning slot.

The recording session of “Being Alive” begins with a few rough takes, before Jones comes into the tech room to discuss. They decide to take the song down tempo. The final take starts a close up, Jones singing through the swirling smoke of a roomful of cigarettes . Even through the dense film grain, you can sense the emotions. And that’s when it clicks. Jones’s attitude shifts suddenly from performing on a record to true feeling. His performance is freeing, triumphant; it’s a song of self-discovery and you can feel every once of it. The song, in that moment, stopped being a composition and started being a performance, a piece of transcendent theatre energy that carried into the recording studio that afternoon. Jones was incredibly talented, but it takes a special spark to perform at a level so inspired. When he’s finished his song, the look on his face is almost confused. He was possessed, in that moment, by the magic of the music and theatre.

A Black & White still of Dean Jones from Original Cast Album: Company

It’s made all the more magical by Pennebaker’s methods, which, through extreme closeups, feels just as genuine as Jones does. He doesn’t add unnecessary cuts, or superficial reactions. He simply holds, even after the song is done. Even a slightly less competent director would’ve cut away, finding the movement more interesting, but Pennebaker is more interested in the people. And that’s his greatest strength.

This filmmaking humanity — mixed with brutal honesty — is also what makes the climatic “Stritch Incident” so intense. It starts with Stritch, more than slightly inebriated, who is the only performer left in the studio, as she attempts “The Ladies Who Lunch.” Her voice is coarse and exhausted, Sondheim knows it, so does everybody else, but she was never going to admit it.

As was made clear in the documentary Elaine Stritch: Shoot Me, Stritch was never going to be one to step down; she would hold her ground in a self-assertive, perhaps over adjusted, chutzpah. In Shoot Me, faced with boundless health struggles, a fading memory, and mounting irritability, Stritch weathers the storm; the show must go on. The perseverance is a testament to her character — and her talent. During her Emmy acceptance speech — she won for Elaine Stritch at Liberty, for which she also won her first (and only_ Tony Award — Stritch, in a blur of words and excitement, yelled, “I had this thing inside me, and thank god I got it out because, if I didn’t, I don’t know what I’d be doing.”

Stritch celebrating her win at the 2004 Emmy Awards

Her reliance on the expression of whatever that thing is what makes it so crushing to watch her struggle, physically and emotionally, through what would become her signature song. The desperation in her eyes is palpable, she wants so badly for the song to come out as it should, but it just won’t. When Shepard informs her that they will have to record the rest of the song another day, you can see her disappointment.

Pennebaker then cuts to the sun rising over the city; the sky is pink, only a handful of buildings have lights on. It’s essentially a throwaway shots, but there’s so much beauty in it. Music fades in, it’s the backing track of “Ladies Who Lunch.” He then cuts to Stritch, on a different day, in a different studio belting out the finale of the song. It was at this moment, I think, it became her anthem. She dances around the room, goofs off with Sondheim, and tells Shepard how she wants her song edited. It’s joyous, to see someone we’ve watched struggle, someone we know struggled throughout her life, get the thing she’s reaching for; when you show a person struggling, you have to show them thriving. It’s the law of tension and release, and, with Original Cast Album: Company, Pennebaker masters it.

Despite being a major document of theatre history — the behind-the-scenes of a show that is widely heralded as one of the greatest musicals — Original Cast Album: Company has fallen through the cracks of time. It was the series pilot of a show that was never produced, it didn’t receive a legitimate HD master until 2021, and it is sadly left out of the pantheon of great documentaries, which it very much deserves to be in.

Few other movies see the truth as clear as this one. Few other films deliver such feelings of triumphant in such a terse runtime. And few other films have the quality of footage that this has. It’s truly very sad that Pennebaker never got the chance to make a second episode. And a third. And a forth. What should have been one of the greatest docu-series in history only left behind a single pilot. But it’s no fun to sit around whining about what could have been. What we got was brilliant. And we should praise what we have.∎

Thank you for enduring my nostalgic ode to a film I love. I hope I’ve inspired at least one person to go check it out, because it’s absolutely worth tracking down.

If you enjoyed this article, why don’t you spread the word!

If you want to hear more from me, enter your email below to get all of my writing directly to your inbox!